Curated by

Giulio Dalvit

Information and tickets

segreteria@santamariadellascala.com

The standard museum admission fee applies.

DISCOUNTS:

- AOU Siena employees: free admission

- Unicoop Firenze membership card holders: €7.00; for groups of more than 10 people: €5.00 each

Opening

Friday, October 24, 5:30 p.m.

On the occasion of the inauguration of the tour, the Provincial Farmers' Union of Siena will offer a tasting of local wines curated by the companies Altesino S.r.l, Caparzo and Azienda Mazza Società Agricola.

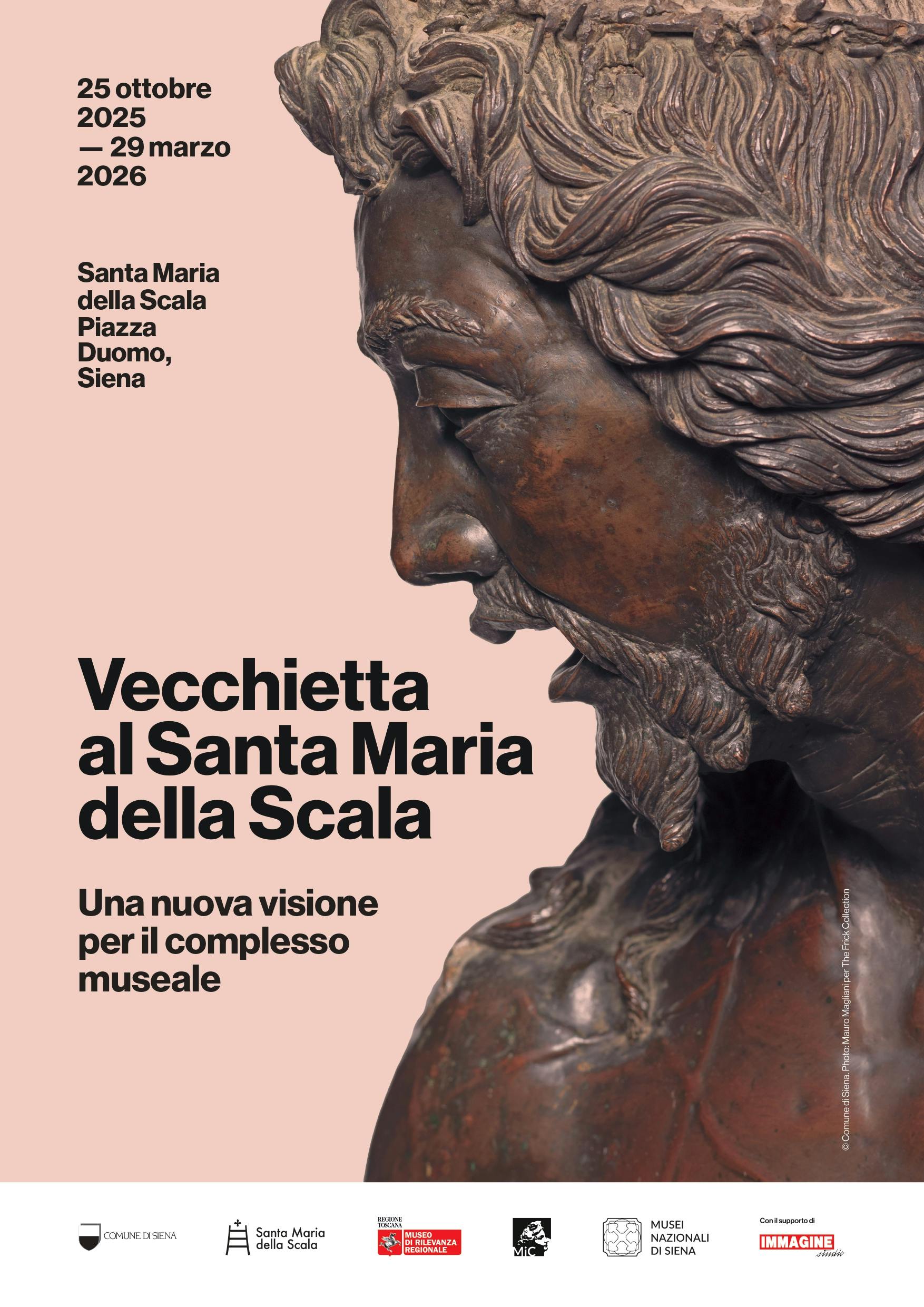

In 2025, just over six hundred years after the birth of Lorenzo di Pietro, known as Vecchietta (Siena, 1410–1480), the Santa Maria della Scala museum complex has decided to reorganize some of its rooms starting from the figure of the artist who worked here more profoundly than any other. Vecchietta worked for more than fifty years for the Hospital. His works—from the Pellegrinaio fresco, to the frescoes in the Old Sacristy, to the bronze ciborium now in the Cathedral—go beyond decoration: they construct a vision and give shape to an identity. It is from this awareness of a unique and foundational relationship that the new setup of the monumental rooms of the Hospital has taken shape. The Old Sacristy (with the Arliquiera reinstated) regains its function as an architectural reliquary and its frescoes are once again legible; the bronze Christ of the Santissima Annunziata, one of the high points of fifteenth-century Italian sculpture, can for the first time be viewed up close. The Pellegrinaio is again the heart of the visit, now cleared of displays that today were considered overly intrusive.

Promoted by Comune di Siena, the project was born from an idea of Cristiano Leone President of the Foundation with curatorship by Giulio Dalvit Associate Curator at the Frick Collection in New York, and also includes the publication of the first critical monograph dedicated to the artist since 1937, entitled Vecchietta, again edited by Giulio Dalvit, available in both English and Italian, which retraces his entire oeuvre, offering a portrait from an updated and international historiographical perspective. The volume is published by Paul Holberton Publishingin London and was produced in collaboration with the Frick Collection in New York and, for the Italian edition, with a contribution from the Fondazione Antico Ospedale Santa Maria della Scala.

The Pellegrinaio

In 1328, the Hospital was expanded with the construction of a men’s pellegrinaio (pilgrim dormitory), which only later, after further work, became known as the “central pellegrinaio.” Under the rectorship of Giovanni di Francesco Buzzichelli (1434–44), this space was transformed into a reception hall: no longer a dormitory, but a place in which the institution displayed, through a monumental cycle of frescoes, its identity and mission. The vaults, with fifty-six saints painted by Agostino di Marsilio, soar above the walls, clearly divided: on the right, Domenico di Bartolo illustrates the daily works of hospital charity; on the left, Vecchietta, Priamo della Quercia, and Domenico himself recount the history of the institution. The last bay was added only in 1577, while the large table by Flaminio Del Turco, made at the start of the seventeenth century, was placed in the hall in 1783. The first episode on the left wall is by Vecchietta: the Vision of the Blessed Sorore (1441), his first signed work. Sorore—a legendary oblate and founder of the Hospital—is kneeling before a canon of the Cathedral. He points to his eyes or forehead, confirming what he sees clearly and what remains invisible to the bystanders: three naked children, souls of the gittatelli rescued by the Hospital, climbing a ladder up to the Virgin, ready to welcome them by the wrists. Invisible to all but two youths at the edge: they are Vecchietta and his brother Nanni, who was also engaged in the pellegrinaio (though in a secondary role). Their presence is not just a flourish, but a statement of role. As the breve of the Guild of Painters declares, the artist is a “revealer of miraculous things”: Vecchietta, unlike the others, must see. He is the channel between the vision and its representation, the one who makes the invisible visible. In his first known work, Vecchietta confronts an unprecedented iconography, understandable only in light of the Hospital’s history. The building, in fact, stands “ante gradus maioris ecclesie,” before the great staircase of the Cathedral: actual steps which affirmed its subordinate position to the cathedral. But even in the hospital’s emblems, the staircase had been reduced to a ladder: in Vecchietta’s fresco, this ladder finally finds its mythical origin—not steps leading to the Cathedral, but a miraculous, vertical ladder, miraculously appearing to the Hospital’s founder. Vecchietta did not continue his work beyond this bay. From 1442, the wall was continued by Domenico di Bartolo and then Priamo della Quercia. Perhaps the artist had left Siena for Castiglione Olona, near Varese, although some scholars place that Lombard stay earlier. In any case, the Hospital never severed ties with him, later entrusting him with the Old Sacristy and the monumental bronze ciborium for the church.

The Old Sacristy

In 1359, the Hospital of Santa Maria della Scala acquired a treasure from afar: a group of relics from the imperial palace in Constantinople—a piece of the Virgin’s veil; a Greek gospel book covered in enamels and gold; even a nail from Christ’s cross, among many others. The entire city welcomed them in procession. For Siena, straddling the Via Francigena, and for the Hospital, it was a masterstroke: the pilgrim now had one more reason to stop (and donate money). In less than a hundred years after the purchase, it was decided to give this treasure a more worthy (and safer) setting than the Cappella del Manto at the end of the church of the Santissima Annunziata, where the relics had previously been held. Between 1445 and 1449, thanks to Vecchietta’s work, the entire room became a gigantic architectural reliquary. The sacristy became a chamber-codex: the Apostles’ Creed (“I believe in God, the Father Almighty, creator of heaven and earth…”) unrolls along the lunettes of the entire room like a painted text, each article flanked by its apostle and, on the lower register, by its Old Testament prefiguration. This is the Concordia Testamentorum: a cycle of unprecedented complexity and erudition. At the center of the vault, a blessing Christ, surrounded by doctors and prophets, and everywhere scrolls, books, inscriptions: the chain of transmission of the word of God—reasserted here against the doubts raised only in 1444 by Lorenzo Valla concerning the apostolic origin of the Creed. Embedded among the frescoes at the end of the arch that still bears its shape was the Arliquiera, a painted wooden cabinet to hold the relics: when closed, it displays a civic pantheon of Sienese saints and blesseds; when opened, it reveals a cycle of the Passion, integrating and completing the frescoes, placing local saints and blesseds (and their martyrdom) in an age-old history of divine revelation. Vecchietta’s long signature at the end of the cycle certifies, together with documentation, his authorship. However, the workshop was collective: two teenagers, Guasparre d’Agostino and Benvenuto di Giovanni, left their cryptic, pseudo-Greek signatures on the cloak of a white-robed figure in the Vision of Daniel in the seventh bay, beneath the Last Judgment. An almost clandestine graffito, but eloquent. Following the expansion of the church in the 1470s (when Vecchietta’s ciborium was placed on the high altar), the sacristy (now “old”) became unusable for that function and was converted into a chapel of the church. In 1476, Francesco di Bartolomeo erected a marble baldachin for an altar, which two centuries later (in 1610) would house the Virgin of Mercy by Domenico di Bartolo, also transported from the Cappella del Manto, of which it was the namesake. The frescoes were whitewashed, and the room degraded over the centuries into a wardrobe, library, schoolroom. Today, in the ruins of its former glory, a feat of imagination is required. But the Old Sacristy remains unique: a total reliquary, a relic in itself. A place where Siena, through Vecchietta, staged the book as Creed, as image, and as political act.

The statue of the Savior (from the artist’s funerary chapel)

In December 1476, Vecchietta wrote to the rector and wise men of the Hospital with an unprecedented request: he wanted a funerary chapel for himself in the Santissima Annunziata, to be dedicated to the Savior. The first artist in Western history to demand such a privilege, he undertook to endow it with two works: an altarpiece with the Madonna and Child with Saints (now in the Pinacoteca Nazionale) and a bronze Savior already begun. The proposal was accepted in February 1477; two years later, in his will, Vecchietta made the chapel his universal heir. Where this chapel was, and what it looked like, is difficult to determine: probably “at the foot of the church,” near the Cappella del Manto, as some ancient sources suggest. Since the width of the church has not changed over the centuries, it probably consisted of a niche in the wall, closed by the altarpiece and preceded by an altar on which stood the Savior: a grouping which, sealing the career of an artist who worked across media, created a sculpto-pictorial Pietà closely resembling a Mass of Saint Jerome (that is, the iconographic subject, common between the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, in which the Church doctor is shown celebrating at the altar while the Crucified comes alive on the altar). This bronze Christ, still at the center of the main altar, is unique. Never before had a monumental, freestanding statue of the Savior been placed on an altar; nor had bronze ever been chosen for such a figure. The Church itself had long been wary of precious statues on altars, fearing the call of pagan idols. Here, supported by the painted altarpiece, Christ brought to the altar the entire Eucharistic power of sacrifice: the crown of thorns on his head, his body exhausted yet capable of crushing the serpent of original sin. Vecchietta, in his seventies, undertook for his own tomb a colossal technical and financial challenge: a devotional act, but also a perpetual monument to his art as painter and sculptor. The chapel soon lost its function. Already by the second quarter of the sixteenth century, and certainly by 1575, the statue had been transferred to the main altar, after Vecchietta’s ciborium was moved to the Cathedral in 1506. Here the Christ was accompanied by the candlestick angels of Accursio Baldi (1500) and, a century and a half later, by the Dead Christ of the antependium by Giuseppe Mazzuoli (ca. 1670). In the eighteenth century, the fresco of the Pool of Bethesda by Sebastiano Conca (1726–27) was painted as its backdrop. Reconfigured as the Risen Christ at the summit of the main altar, Vecchietta’s Christ remained too little known, by both the public and scholars. But it endures, in the heart of Santissima Annunziata, as one of the high points of Italian Renaissance sculpture—now, finally, accessible*.

*Visits to the statue of the Savior are temporarily suspended.

For information: segreteria@santamariadellascala.com

Locations

The Old Sacristy

In the 1340s, during a period of extraordinary historical significance for Siena and its main hospital, in an atmosphere of great cultural, religious, and political ferment, the assisting and religious spaces of Santa Maria della Scala were extensively renovated and enriched with decorative elements, paintings, furnishings, and chapels, to the extent that the hospital became one of the most important centers of artistic production of the early Sienese Renaissance.

In the 1340s, during a period of extraordinary historical significance for Siena and its main hospital, in an atmosphere of great cultural, religious, and political ferment, the assisting and religious spaces of Santa Maria della Scala were extensively renovated and enriched with decorative elements, paintings, furnishings, and chapels, to the extent that the hospital became one of the most important centers of artistic production of the early Sienese Renaissance.

The Pellegrinaio

In 1328, the hospital expanded its structure with the construction of a male pilgrim's hostel, achieved through the acquisition and demolition of surrounding houses to overcome a height difference of three stories.

In 1328, the hospital expanded its structure with the construction of a male pilgrim's hostel, achieved through the acquisition and demolition of surrounding houses to overcome a height difference of three stories.

Church of the Santissima Annunziata

The church of the Santissima Annunziata, oriented longitudinally with respect to the square, today occupies much of the facade of the hospital. Numerous interventions and transformations have characterized its history, as well as the furnishings and works commissioned for it, some of which are still preserved within its structure, but also those of which traces remain in the rich hospital documentation or in the iconographic tradition.

The church of the Santissima Annunziata, oriented longitudinally with respect to the square, today occupies much of the facade of the hospital. Numerous interventions and transformations have characterized its history, as well as the furnishings and works commissioned for it, some of which are still preserved within its structure, but also those of which traces remain in the rich hospital documentation or in the iconographic tradition.